The Story of Henrietta Lacks - and her Immortal Cells

|

the disease. They gave some of that tissue to a researcher without Lacks’s knowledge or consent.

In the laboratory, her cells turned out to have an extraordinary capacity to survive and reproduce; they were, in essence, immortal. The researcher shared them widely with other scientists, and they became a workhorse of biological research. Today, work done with HeLa cells underpins much of modern medicine; they have been involved in key discoveries in many fields, including cancer, immunology and infectious disease. One of their most recent applications has been in research for vaccines against COVID-19.

This is a tale of a poor black tobacco farmer who never consented to having her tissues taken but whose cancer cells have proved so important they have formed the foundation for work leading to two Nobel prizes.

The cells taken from her have been used in experiments all over the world and even in space. HeLa cells have helped make hundred of millions of profits for companies all over the world and been used for medical breakthrough after breakthrough. They have been used to develop the polio vaccine and in vitro fertilisation and even cloning.

Yet Lacks's family never knew about it – even as the cells were used around the world in research, or when they themselves were asked for blood samples two decades later.

None of the biotechnology or other companies that profited from her cells passed any money back to her family.

world's most expensive drug Zolgensma

Zolgensma: What it is and why the cost

It costs Rs 18 cr a dose

This drug, which was first approved on May 24, 2019 by the US Food and Drug Administration, was approved by the United Kingdom's National Health Services (NHS) on March 9, 2020. It is manufactured by US-based Swiss bio-pharmaceutical company Novartis Gene Therapies.

"Spinal Muscular Atrophy is the leading genetic cause of death among babies and young children, which is why NHS England has moved mountains to make this treatment available, while successfully negotiating behind the scenes to ensure a price that is fair to taxpayers," he added.

Spinal Muscular Atrophy is a rare hereditary disease caused by one missing gene or the deficiency of a functional survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene, according to Novartis. This results in rapid and irreversible loss of motor neurons, affecting main muscle functions like breathing, swallowing and basic movements. Since these neurons control muscle movement throughout the body, a lack of it could cause paralysis, severe muscle weakness and loss of movement. The prevalence of SMA is about 1 in 10,000 children. 1 in 54 people carry the genetic defect of SMA and two carriers have a 25% chance of having a child with SMA.

Zolgensma is the second and most effective drug for the disorder. The reason for its exorbitant cost is its miniscule market size in the drug manufacturing industry and its potential to save lives. "The disorder is rare and that is why we needed a highly specialized drug. The expertise required to make it and the research around it has taken very long. It's also a one-time dose; the fewer the cases the higher its price will be. Discovering and manufacturing a new drug can costs billions of dollars.

How will Zolgensma treat SMA?

According to the NHS, the drug contains a replica of the missing gene. The active ingredient onasemnogene abeparvovec passes into the nerves and restores the gene, which then produces proteins necessary for nerve function and controlling muscle movement. The dose is determined based on the weight of the patient. "This drug is a one-time intravenous infusion which is administered on a patient for over an hour and is used to treat children under two years of age," Desai said. A common side effect in patients is rise in liver enzymes, according to Desai. As per the safety guidelines of Novartis, those with pre-existing liver conditions are particularly at risk of acute liver injury and tests should be conducted to assess liver function prior to the treatment with Zolgensma.

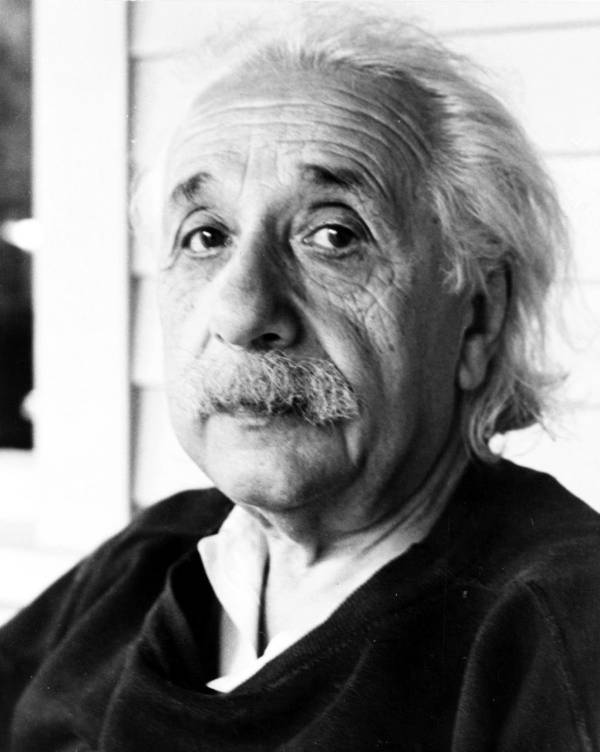

Death Of Albert Einstein — And The Strange Afterlife Of His Brain

|

Before Albert Einstein died in April 1955, he told his family he didn't want to be studied. But hours after he perished, a medical examiner stole his brain for research. When Albert Einstein was rushed to the hospital in 1955, he knew that his end was near. But the 76-year-old famed German physicist was ready, and he informed his doctors with all the clarity of a math equation that he would not like to receive medical attention. |

“I want to go when I want,” he said. “It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share, it is time to go. I will do it elegantly.” When Albert Einstein died of an abdominal aortic aneurysm on April 17, 1955, he left behind an unparalleled legacy. The frizzy-haired scientist had become an icon of the 20th century, befriended Charlie Chaplin, escaped Nazi Germany as authoritarianism loomed, and pioneered an entirely new model of physics. Einstein was so revered, in fact, that just hours after his death his inimitable brain was stolen from his corpse — and remained stashed away in a jar in a doctor’s home. Though his life has been dutifully chronicled, Albert Einstein’s death and the bizarre journey of his brain afterward deserve an equally meticulous look.

Einstein was born on March 14, 1879, in Ulm, Württemberg, Germany. Before he developed his theory of general relativity in 1915 and won the Nobel Peace Prize for Physics six years after that, Einstein was just another aimless middle-class Jew with secular parents.

As an adult, Einstein recalled two “wonders” that deeply affected him as a child. The first was his encounter with a compass when he was five years old. This birthed a lifelong fascination with the invisible forces of the universe. His second was the discovery of a geometry book when he was 12, which he adoringly called his “sacred little geometry book.” Also around this time, Einstein’s teachers infamously told the restless youth that he would amount to nothing.

Undeterred, Einstein’s curiosity about electricity and light grew stronger as he grew older, and in 1900, graduated from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. Despite his inquisitive nature and academic background, however, Einstein struggled to secure a research position. After years of tutoring children, the father of a lifelong friend recommended Einstein for a position as a clerk in a patent office in Bern. The job provided the security Einstein needed to marry his long-term girlfriend, with whom he had two children.

Meanwhile, Einstein continued to formulate theories about the universe in his spare time. The physics community initially ignored him, but he garnered a reputation by attending conferences and international meetings. Finally, in 1915, he completed his general theory of relativity, and just like that, he was spirited around the globe as a lauded thinker, rubbing elbows with academics and Hollywood celebrities alike.

On his final day, Einstein was busy writing a speech for a television appearance commemorating the State of Israel’s seventh anniversary when he experienced an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), a condition during which the body’s main blood vessel (known as the aorta) becomes too large and bursts. Einstein had experienced a condition like this before and had it surgically repaired in 1948. But this time, he refused surgery. When Albert Einstein died, some speculated that his cause of death could have been correlated with a case of syphilis. According to one doctor who was friends with the physicist and wrote about the death of Albert Einstein, AAA can be instigated by syphilis, a disease some thought that Einstein, who was “a strongly sexual person,” could have contracted. However, no evidence of syphilis was found in Einstein’s body or brain in the autopsy that followed his death.

But Albert Einstein’s cause of death could have been exacerbated by another factor: his lifelong smoking habit. According to another study, men who smoked were 7.6 times more likely to experience a fatal AAA. Even though Einstein’s doctors had told him to quit smoking various times throughout his life, the genius rarely hung up the vice for long.

His Brain Was Notoriously ‘Stolen’

Hours after he passed, the doctor who performed the autopsy on the corpse of one of the world’s most brilliant men removed his brain and took it home without the permission of Einstein’s family. His name was Dr. Thomas Harvey, and he was convinced that Einstein’s brain needed to be studied as he was one of the most intelligent men in the world. Even though Einstein had written out instructions to be cremated upon death, his son Hans ultimately gave Dr. Harvey his blessing, as he evidently also believed in the importance of studying the mind of a genius.

Harvey meticulously photographed the brain and sliced it into 240 chunks, some of which he sent to other researchers, and one he tried to gift Einstein’s granddaughter in the ’90s — she refused. Harvey reportedly transported parts of the brain across the country in a cider box that he kept stashed under a beer cooler. In 1985, he published a paper on Einstein’s brain, which alleged that it actually looked different from the average brain and therefore functioned differently. Later studies, however, have disproved these theories, though some researchers maintain that Harvey’s work was correct.

Meanwhile, Harvey lost his medical license for incompetency in 1988.